To begin, if you would please take a minute to think back to the moment you met the last person you truly fell in love with. Close your eyes and notice how vivid you can make the memory. Do you remember exactly how their face looked or the way they smelled? Chances are some pretty clear details still remain no matter how long ago it was. Now, ask yourself, “Why was it that I fell in love with this person?” Was it the fact that they had a good job and similar interests, was it something ineffable, something you might call chemistry or soulmates, or perhaps all of the above?

To begin, if you would please take a minute to think back to the moment you met the last person you truly fell in love with. Close your eyes and notice how vivid you can make the memory. Do you remember exactly how their face looked or the way they smelled? Chances are some pretty clear details still remain no matter how long ago it was. Now, ask yourself, “Why was it that I fell in love with this person?” Was it the fact that they had a good job and similar interests, was it something ineffable, something you might call chemistry or soulmates, or perhaps all of the above?

Why the experience of falling in love is so intense and meaningful, why we choose to fall in love with who we do, and whether or not we can stay in love over many years, are likely questions humans have wrestled with for as long as we have been able to consider them.

The experience of both falling in love and being rejected in love leaves a lasting imprint on our psyche as they speak to some of the most fundamental aspects of what it means to be human.

Now, take a moment to ask whether you or anyone you know has ever arrived at any sort of a satisfying answer to these questions? Chances are that some big gaps exist in your understanding. I know they did for me. Fortunately, the very accomplished Helen Fisher, PhD a Biological Anthropologist, Senior Research Fellow at The Kinsey Institute, member of the Center for Human Evolutionary Studies in the Department of Anthropology at Rutgers University, Chief Scientific Advisor to the Internet dating site Match.com, and author of six books on love, sex, and relationship, thinks she has discovered some of the biological underpinnings of why we fall in love and who we “choose” to fall in love with.

Though there are many ways of looking at who we choose to love, such as a spiritual connection through past lives, or the psychologically driven tendency to fall in love with individuals that trigger familiar childhood wounds–so we may heal them–this article focuses specifically on illuminating evolutionary biology’s influence on the process of falling in love and the choice of whom to fall in love with. If learning about how your brain influences your love life and how to utilize this understanding both in and out of love interests you, then please read on . . .

Modern Times: The Return of Romantic Love and the Paradox of Choice

To begin this exploration let’s compare our current ideas, practices, and trends about dating and love with those of the past, including the very distant past . . .

We are in the midst of a drastic shift in how, who, and for what reasons we choose a partner. In many ways we have, within just a few generations, moved away from the predominantly social reasons that have dominated the last 10,000 years (post agricultural revolution) such as ethnic group, social class, religion, and family gain, and into an era of choosing for ourselves and for love. Contrary to popular belief, this is not as much of a new era of love for our species as it is a return. Though we certainly had far less choice than say 40,000 years ago when we lived as hunter gatherers in tribes of 20-50 individuals than we do today, it seems that prior to the agricultural revolution (the bulk of human evolution), that the drive of romantic love was quite operational and largely running the show. It is likely that this did not often result in happy lifelong marriages, but that this coupling lasted long enough to raise children to an age where they could survive with the care of their peers and relatives, which Fisher notes likely averaged around four years. Regardless of the length of the union, it is important to note that as a species we have as a reproductive strategy evolved to form pair bonds, i.e.—monogamy. However, evidence shows that as a species we are also adulterous. This duel reproductive strategy can appear to be at odds with itself in modern times. Fisher even goes so far as to state that, “Our drive to commit vs our drive for autonomy is one of the great challenges of this century.” However, this dual strategy has its roots in our evolutionary history, the understanding of which can bring some much-needed clarity.

Choice Paralysis in the Modern Dating Scene

In his book The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less American psychologist Barry Schwartz points out that when it comes to choice, more often equals less. We experience less satisfaction with our choice when we have many choices to choose from and we experience more anxiety in the act of choosing. Schwartz’ work centers around the consumer experience, e.g.—walking down the cereal aisle and having a choice induced existential crisis—however, one could argue that with the explosion of choice in today’s dating scene, fueled by the many popular online dating services, that Schwartz’s findings apply equally to this area of our lives.

If like many, you often find yourself overwhelmed by the amount of choice in the dating world and perhaps have a persistent little voice in the back of your mind whispering, “The grass looks a lot greener over there, you could do better,” wouldn’t it be nice to know if something else, something beyond your conscious mind, could weigh in? Let’s take a deeper look at some of Helen Fisher’s findings . . .

The Romantic Love Drive

The reason why it is so difficult to control feelings of romantic love is in part because it is a basic drive.

The romantic love drive evolved hundreds of thousands of years ago and is predominantly a dopamine brain pathway, a brain circuit that is deep below the cortex at which we do our conscious thinking, and below the limbic system where the central organizations of the emotions happens. This pathway is actually found at the very base of the brain, meaning it is far beneath the conscious mind and a structure that evolved long long ago, compared to the rest of the brain.

In our modern times we are essentially abandoning the last 10,000 years and returning to an old way of coupling, which places the drive of romantic love at the center. The difference however is that we find ourselves in a significantly new and different environment, which as mentioned above, consists of nearly infinitely more choice as well as far higher expectations for happiness and longevity.

Though this return comes with many benefits, such as healthier relationships that both individuals actually want to be in and can leave if it’s not working, without severe economic or social consequences, it is also quite a new phenomenon within the context of the modern era. What neuroscience is beginning to make very clear is that an ancient brain system operating in a totally new modern environment can create a lot of confusion, pain, anxiety and, in this case, heartbreak.

To understand the biological underpinnings of who we choose as a mate we first have to understand what happens when we fall in love and, at least from an evolutionary standpoint, and why we fall in love. Fisher notes that the experience of falling in love has its biological basis in the aforementioned romantic love drive, which is actually one of the three drives that make up the human coupling and reproductive brain system, the others of which are the sex drive and the attachment drive.

Evolutionarily speaking, the sex drive is there to ensure that we will get out there and seek novel mates and the attachment drive ensures a lasting bond of care between parent and child and between romantic partners, at least long enough to raise a healthy child. Seen through the lense of neurobiology, the romantic love drive exists to focus our energy on one person in order to carry out our monogamous reproductive strategy. This is a very strong drive, as Fisher notes that, “Romantic love is as powerful as thirst and hunger.” Certainly songs have been written and poetry has been made that pays homage to the sex and attachment drives, but by far the most compelling throughout the ages has been the experience of romantic love.

What Happens When We Fall in Love?

One of the first things you might notice when you fall in love is that the person you are falling in love with takes on a special meaning. Anything from their choice in music, to fashion, to how they laugh or smile becomes special. Many people also report feeling an incredible amount of energy, so much so that walking all night and talking till dawn (or other nocturnal activities) seems to have little effect on one’s ability to function in daily life. Many also experience other bodily reactions, especially early on, such as a dry mouth, butterflies and weak knees. On the darker side, sexual possessiveness is another hallmark of romantic love as well as the experience of separation anxiety. In a sense, within the throes of the romantic love, the other is object of your craving.

One of the first things you might notice when you fall in love is that the person you are falling in love with takes on a special meaning. Anything from their choice in music, to fashion, to how they laugh or smile becomes special. Many people also report feeling an incredible amount of energy, so much so that walking all night and talking till dawn (or other nocturnal activities) seems to have little effect on one’s ability to function in daily life. Many also experience other bodily reactions, especially early on, such as a dry mouth, butterflies and weak knees. On the darker side, sexual possessiveness is another hallmark of romantic love as well as the experience of separation anxiety. In a sense, within the throes of the romantic love, the other is object of your craving.

Fisher breaks the romantic love drive down into three distinct parts, craving for emotional union, obsessive thinking, and a high level of motivation to win the other over; all of which make up a predictable pattern demonstrated by people falling in love time and time again. Much of this experience seems to be out of our conscious control because it has such a strong biological component. What is especially fascinating is that when analyzing the brains of those in love the picture looks astonishingly like addiction. In fact Fisher states that romantic love “is one of the most powerful addictions the human animal has ever experienced.”

In fact, the more commonly recognized addictions of today would have little effect without the brain pathways established in our ancient biology by the romantic love drive.

In understanding the brain in love it is important to note that the nucleus accumbens, the same brain region that becomes active when you crave the likes of heroin, cocaine, alcohol, nicotine, food, or gambling also becomes active when you are madly in love, and when you have been rejected in love. In a certain sense, falling in love is a healthy addiction that, when it goes well, can lead to positive feelings of intimacy, connection and a lasting bond–when the attachment drive takes over. However, when it goes poorly it is a very painful experience. Arguably, the experience of rejection, or love lost, has even more art, music and poetry devoted to the unique type of anguish it produces.

In understanding the brain in love it is important to note that the nucleus accumbens, the same brain region that becomes active when you crave the likes of heroin, cocaine, alcohol, nicotine, food, or gambling also becomes active when you are madly in love, and when you have been rejected in love. In a certain sense, falling in love is a healthy addiction that, when it goes well, can lead to positive feelings of intimacy, connection and a lasting bond–when the attachment drive takes over. However, when it goes poorly it is a very painful experience. Arguably, the experience of rejection, or love lost, has even more art, music and poetry devoted to the unique type of anguish it produces.

Unfortunately, the romantic love drive did not evolve to protect us from the pain of rejection. This is because, in the eyes of our evolution and the propagation of our species, the risk is less than the reward. In other words, taking the risk of rejection is always worth the potential reward of a healthy offspring in the eyes of the romantic love drive. This doesn’t make it any less painful however, as nearly identical brain centers light up in the experience of say a broken bone as a broken heart. This is because our brains do not distinguish the difference between emotional and physical pain and thus the experience can feel much the same. If one approaches the mending of broken heart with the same compassion that a broken leg might evoke it will likely be easier to heal. Furthermore, by taking into account the chemically addictive process of the romantic love drive, it makes the greatest sense to go “cold turkey.” In other words, to help your brain recover from the turmoil of romantic love, Fisher notes that it is helpful to treat the process as an addiction and remove any triggers for that addiction, such as texts, cards, pictures and spend three to six months with little to no contact. This gives the brain a chance to reset and for the drive of romantic love to return to balance.

Unfortunately, the romantic love drive did not evolve to protect us from the pain of rejection. This is because, in the eyes of our evolution and the propagation of our species, the risk is less than the reward. In other words, taking the risk of rejection is always worth the potential reward of a healthy offspring in the eyes of the romantic love drive. This doesn’t make it any less painful however, as nearly identical brain centers light up in the experience of say a broken bone as a broken heart. This is because our brains do not distinguish the difference between emotional and physical pain and thus the experience can feel much the same. If one approaches the mending of broken heart with the same compassion that a broken leg might evoke it will likely be easier to heal. Furthermore, by taking into account the chemically addictive process of the romantic love drive, it makes the greatest sense to go “cold turkey.” In other words, to help your brain recover from the turmoil of romantic love, Fisher notes that it is helpful to treat the process as an addiction and remove any triggers for that addiction, such as texts, cards, pictures and spend three to six months with little to no contact. This gives the brain a chance to reset and for the drive of romantic love to return to balance.

Let Your Brain Help You Make the Choice

And now the part you have probably been waiting for . . . Why do we fall in love with one person and not another? This is the exact question that Fisher asked herself when beginning her research. There were already studies that demonstrated that people tend to fall in love with individuals with similar general levels of intelligence, economic backgrounds, social values, good looks, etc. As well as studies demonstrating the impact childhood makes on our choice of a partner, such as the creation of an unconscious list of what you are looking for in a partner. However, Fisher wanted to know why it is that when you walk into a room with 15 people that all have these similar qualities and meet your unconscious criteria, do you fall in love with one and not another. She suspected a biological component at work. In speaking about the initial phase of her research Fisher notes that, “People say that we have or we don’t have chemistry, and I wondered what that meant, I wanted to know are we biologically pulled to one another, not just culturally pulled.” What Fisher soon discovered is quite groundbreaking.

And now the part you have probably been waiting for . . . Why do we fall in love with one person and not another? This is the exact question that Fisher asked herself when beginning her research. There were already studies that demonstrated that people tend to fall in love with individuals with similar general levels of intelligence, economic backgrounds, social values, good looks, etc. As well as studies demonstrating the impact childhood makes on our choice of a partner, such as the creation of an unconscious list of what you are looking for in a partner. However, Fisher wanted to know why it is that when you walk into a room with 15 people that all have these similar qualities and meet your unconscious criteria, do you fall in love with one and not another. She suspected a biological component at work. In speaking about the initial phase of her research Fisher notes that, “People say that we have or we don’t have chemistry, and I wondered what that meant, I wanted to know are we biologically pulled to one another, not just culturally pulled.” What Fisher soon discovered is quite groundbreaking.

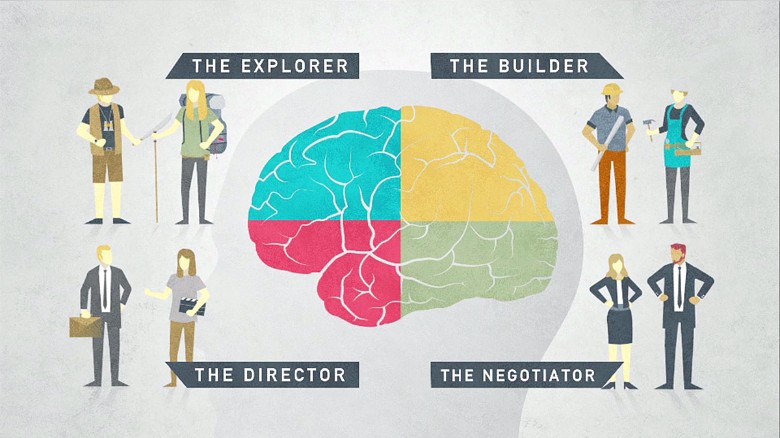

In her research, Fisher found four unique biologically based brain systems that she was able to link with specific personality traits. These findings are of particular interest because, to the best of my knowledge, this is the only personality typing system that is scientifically researched, peer reviewed, and has been shown to have a biological basis. The four systems are as follows:

- Dopamine (The Explorer): Novelty seeking, risk taking, curious, energetic, makes and looses the most money, impulsive, idea generator.

- Serotonin (Builders): Likes the familiar, calm, follows social norms, plans, routines, schedules, concrete thinking, literal, follows the rules, loyal.

- Testosterone (Director): Analytical, competitive, rank oriented, logical, emotionally contained, decisive, bold, demanding.

- Estrogen (Negotiator): web thinking (sees big picture), intuitive, trusting, able to read others, everything has meaning, seeks harmony, emotionally expressive.

Though we have all four systems operating within us, Fisher found that in each individual one or two tend to be dominant, which show up in how the personality is expressed. She also began to notice a pattern emerging among the types; certain ones tended to predictably pick similar types as romantic partners. For example, dopamine and serotonin dominated personality types tended to pick their same type for partners, and the testosterone and estrogen types tended to pick each other. Fisher took these initial findings and developed an online questionnaire to help individuals determine their dominant brain system in order to gather far more data than was possible in her initial study. The questionnaire has now been taken by over 14 million people and can be taken for free online here.

Neurobiology in Action

How can this knowledge help you? Well, for starters if a romantic relationship in which you were in love has recently ended, you may now be able to use the knowledge of the similarities between romantic love and addiction to have more compassion for yourself in the very painful withdrawal phase. Also, if you feel overwhelmed by the amount of choice in the dating scene today then you may be able to relax a bit more knowing that your brain is on the job and actually has a lot of input below your conscious mind. Similarly, if you find yourself experiencing the pain and confusion of falling in love with someone who you know is not a healthy partner for you, you may now have an increased understanding of this situation.

You may be able to understand that this initial phase of relationship, dominated by the ancient and very powerful romantic love drive, is in part biologically driven and something that can, and in certain situations, should be overridden by your conscious mind.

I also find this information somewhat helpful in explaining the mysterious component of chemistry involved in falling in love. If, for example, you don’t fall in love when you think you should or even want to, you could get upset or have some compassion and allow that to be alright.

Healthy Relationships

Finally, let’s take a look at few tips for what makes a healthy relationship, so you can not only have a greater understanding of falling in love but also how to turn that into a long lasting partnership, if that’s what you are wanting. Firstly, I want to point out that the evidence suggests that you can in fact remain in love long term. Though it isn’t always easy, in a healthy romantic relationship all three key drives (sex, romantic, attachment), can remain in play. In other words, you can have a real sexual interest in your partner, regularly feel the rush of romance, and feel a deep sense of care and attachment to them for many years. In relationships such as these, Fisher discovered a few common threads which include:

Finally, let’s take a look at few tips for what makes a healthy relationship, so you can not only have a greater understanding of falling in love but also how to turn that into a long lasting partnership, if that’s what you are wanting. Firstly, I want to point out that the evidence suggests that you can in fact remain in love long term. Though it isn’t always easy, in a healthy romantic relationship all three key drives (sex, romantic, attachment), can remain in play. In other words, you can have a real sexual interest in your partner, regularly feel the rush of romance, and feel a deep sense of care and attachment to them for many years. In relationships such as these, Fisher discovered a few common threads which include:

- Real empathy for one another other.

- Each individual having the ability to manage stress and emotions.

- Positive illusions: Each individual having the ability to overlook what you don’t like in the other and focus on what you do like.

Lastly Fisher notes that if you treat your partner as they want to be treated, and not how you want to be treated, you will create the foundation for a healthy romance filled long-term relationship.

If you are currently in a relationship or want your next one to be healthier and happier, and feel some or all of these qualities are missing or underdeveloped in you and or your partner, the good news is that they can be cultivated. As a counselor I regularly help couples and individuals discover the obstacles that obstruct more empathy and compassion for self and other, as well as the cultivation of healthy emotional release and regulation. Additionally, with the power of love languages (see previous article Why Are We Still Fighting?), and the use of attachment theory, I help teach individuals how to recognize and express their own needs, meet their partners needs, and form a lasting healthy interdependent bond. The result of which leads to greater and greater levels of relationship satisfaction. I also provide support for grieving the loss of love and a broken heart. If you want to take action I encourage you to reach out to a counselor and go on a journey toward the relationship you want.

If you are currently in a relationship or want your next one to be healthier and happier, and feel some or all of these qualities are missing or underdeveloped in you and or your partner, the good news is that they can be cultivated. As a counselor I regularly help couples and individuals discover the obstacles that obstruct more empathy and compassion for self and other, as well as the cultivation of healthy emotional release and regulation. Additionally, with the power of love languages (see previous article Why Are We Still Fighting?), and the use of attachment theory, I help teach individuals how to recognize and express their own needs, meet their partners needs, and form a lasting healthy interdependent bond. The result of which leads to greater and greater levels of relationship satisfaction. I also provide support for grieving the loss of love and a broken heart. If you want to take action I encourage you to reach out to a counselor and go on a journey toward the relationship you want.

Thank you for reading.

Till next time,

Dan Entmacher MA, LPCc

For More information on this topic take a look at TheAnatomyofLove.com and Helen Fisher’s Ted Talk: