What is Trauma?

The word trauma is thrown around a lot these days. For example, you may have heard a friend refer to their family reunion as “absolutely traumatizing.” But what exactly is trauma, and what differentiates it from simply a stressful situation? Also, What makes the same event traumatizing for one person and not for another? In this article I will attempt to answer these questions by defining psychological trauma, the varying ways it affects those who experience it, as well as lay out how people recover from it’s effects, including Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

The word trauma is thrown around a lot these days. For example, you may have heard a friend refer to their family reunion as “absolutely traumatizing.” But what exactly is trauma, and what differentiates it from simply a stressful situation? Also, What makes the same event traumatizing for one person and not for another? In this article I will attempt to answer these questions by defining psychological trauma, the varying ways it affects those who experience it, as well as lay out how people recover from it’s effects, including Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

Essentially,

psychological trauma occurs when an event or series of events, that are perceived as life threatening, overwhelm our instinctive coping strategies and integrative capacities.

Simple right? Let me explain further . . .

The Story of Trauma Tom

Let’s say that, for example, a persons home is broken into at night; let’s call this person Tom. Tom hears a noise, gets up and finds a masked intruder inside his home. This person then threatens Tom with violence if he doesn’t give them what they’re asking for. Tom’s first impulse is to reason with this person, to appeal to their humanity, and calm down the situation with words. This strategy is often our first line of defense, and in psychological terms, is known as the Social Engagement System (SES). But perhaps with just the first few words uttered out of Tom’s mouth the intruder screams at Tom to give them all his valuables or they are going to kill him.

Let’s say that, for example, a persons home is broken into at night; let’s call this person Tom. Tom hears a noise, gets up and finds a masked intruder inside his home. This person then threatens Tom with violence if he doesn’t give them what they’re asking for. Tom’s first impulse is to reason with this person, to appeal to their humanity, and calm down the situation with words. This strategy is often our first line of defense, and in psychological terms, is known as the Social Engagement System (SES). But perhaps with just the first few words uttered out of Tom’s mouth the intruder screams at Tom to give them all his valuables or they are going to kill him.

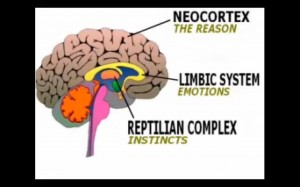

Okey, so the SES didn’t work so well here. Now Tom instinctively moves on to the Fight or Flight defensive system, which is produced by a heightened state of arousal in his Sympathetic nervous system. Tom quickly scans the environment for usable weapons and before he knows what he’s doing decides that a golf club against a loaded gun is not a good idea. Then he scans the environment for an easy exit. There is none. The intruder quickly becomes enraged and starts to come at Tom. Tom tries to defend himself (Fight) and get away from the intruders grasp (Flight) but he is unable to do either. Tom then begins to panic and go into a state of Freeze. Freeze, as well as Feign Death, is a last ditch effort of humans old reptilian brain to protect our conscious minds from a situation that can’t really be defended against and overwhelms our defenses. Tom now feels oddly disconnected from his body, which is being assaulted. Then he blacks out from a blow to the head. Tom comes to an hour or so later feeling strange. He notices that he’s hurt but he only has a spotty recollection of the events that just occurred.

What Just Happened and Was That a Trauma?

In this example we see Tom attempting to utilize the first three lines of defense against a threat, the coping strategies of the social engagement system, fight, and flight. When these fail to stop the threat he moves on to freeze, which then causes the Parasympathetic part of his nervous system to go into overdrive. In Tom’s example, this is essentially the nervous system equivalent of going from 120 MPH to slamming on the breaks. Extreme states of freeze can cause dissociation. We saw this when Tom experienced a sense of being outside of his body.

Dissociation is actually an ingenious coping strategy of the brain to protect the individual from the worst forms of violence and pain.

However, freeze and dissociation are not without their consequences.

If the first three coping strategies fail to evade a threat and freeze kicks in, we can now consider this event traumatizing. When someone enters into a state of freeze during a life-threatening event it is very likely that they will experience prolonged adverse effects of trauma, including symptoms of PTSD. Let’s return to Tom’s story to illustrate the aftermath of trauma.

The Aftermath . . .

It is now four months later and Tom is concerned because he is struggling to get through his day-to-day. Where before he had been a successful and confident business owner and father, he now finds himself being thrown into states of panic when he sees anyone wearing anything resembling a black ski mask or a star tattoo, both of which were visible on his assailant. Tom’s relationship with his family is also suffering. He is unable to relax at home and his kids are confused and hurt that their father doesn’t seem to want to spend time with them anymore. Tom also finds himself quickly flipping from states of hypo-arousal, where he is on the alert for danger and experiences intrusive feelings of anxiety and body sensations of panic, along with memories of the event, to hypo-arousal, where he feels numb and disconnected. Tom is confused because he feels that he should be able to “handle it” and he is starting to feel ashamed. Eventually Tom’s family insists that he get help because nothing is getting better.

Responding to Threat

What makes one person experience a threatening event as traumatizing and not another is a fairly complex question. In the simplest terms it has to do with one’s level of resources and integrative capacity, in other words their ability to stay out of the freeze response, stay in the social engagement system, and store the memories in the Temporal Cortex (more on this later). There are many factors that influence one’s ability to do this, some of which have to do with the type of experience. If the threat was recurring and inflicted by a primary caregiver, it becomes much harder to walk away untraumatized. Also, an individual’s past has a lot to do with how they might respond to a current threat. If they have a history of trauma, especially during childhood, a trauma response becomes much more likely in reaction to a new threat. Attachment, a term used to describe one’s emotional bond with their primary caregiver/s, also has a huge impact on one’s integrative capacity. Though a full explanation of attachment is beyond the scope of this article, suffice it to say that people with secure attachment generally have more resources at their disposal to deal with threatening events. For a more in depth look at attachment take a look at my post Why Do Breakups Hurt So Much?

An Act of Triumph: Recovering from Trauma

Over the past 10-20 years there has been a growing body of research on the effects of trauma. This research has greatly deepened our understanding of trauma recovery. There are now many forms of trauma therapy grounded in neuroscience and practiced all over the world. The form of treatment I have seen the most success with, and the form that I practice, is called Sensorimotor Psychotherapy. In this modality, pioneered by Pat Ogden Ph.D, trauma is healed through a body-centered (somatic) approach.

Over the past 10-20 years there has been a growing body of research on the effects of trauma. This research has greatly deepened our understanding of trauma recovery. There are now many forms of trauma therapy grounded in neuroscience and practiced all over the world. The form of treatment I have seen the most success with, and the form that I practice, is called Sensorimotor Psychotherapy. In this modality, pioneered by Pat Ogden Ph.D, trauma is healed through a body-centered (somatic) approach.

Trauma & Memory

The first part of trauma recovery involves an understanding of how our memory works. It may be surprising to know that memories of traumatic events become stored in an entirely different part of the brain than normal memory. Normal memory, that which can be recalled and accessed at will, is known as explicit memory, and is stored in the temporal cortex. There is a good deal of evidence that suggests that traumatic memory is stored within the limbic and sensorimotor parts of the brain in a process called implicit memory. This form of memory is equally important to a healthy brain and can be thought of as “unconscious memory.” Implicit memory helps us remember important things like how to ride a bicycle. However, when traumatic memories are stored here, because they are too painful and overwhelming for the conscious mind to digest, they are remembered not at will but through association triggers. These triggers, such as similar smells or images to those experienced during the traumatic event, bring up an aspect of the memory from our unconscious to our conscious mind and is experienced not as memory but as an event occurring in the present moment.

The term some use for these intrusive implicit memories is flashback, which is one of the reasons why PTSD can have such a harmful and destabilizing impact on people’s daily lives.

In successful treatment, traumatic memories must be worked with differently than explicit ones. For example, the triggering of traumatic memories can cause someone to go outside their nervous systems’ window of tolerance, which is essentially their ability to stay present and in contact with the therapist while working with traumatic memories. As soon as one leaves the window, their nervous system is in hyper or hypo arousal and they are at risk for re-experiencing the trauma instead of healing from it. Special care is taken in Sensorimotor Psychotherapy to expand an individual’s window of tolerance as well as teach monitoring skills to ensure the client stays within their window.

In successful treatment, traumatic memories must be worked with differently than explicit ones. For example, the triggering of traumatic memories can cause someone to go outside their nervous systems’ window of tolerance, which is essentially their ability to stay present and in contact with the therapist while working with traumatic memories. As soon as one leaves the window, their nervous system is in hyper or hypo arousal and they are at risk for re-experiencing the trauma instead of healing from it. Special care is taken in Sensorimotor Psychotherapy to expand an individual’s window of tolerance as well as teach monitoring skills to ensure the client stays within their window.

Defensive Responses

The second part of understanding trauma recovery includes interrupted/incomplete defensive responses. These responses are essentially what the initial coping strategies wanted to do, which is escape the threat through social engagement, and if that doesn’t work then through fighting or fleeing. If we recall that trauma occurs when these strategies are overwhelmed and become ineffective, it makes some sense to imagine that the impulses of these strategies become stored in the brain along with the traumatic memory. In Tom’s example, this may be his body’s impulse to successfully push his attacker away and run out the back door.

These interrupted defensive responses must be addressed in trauma recovery and if not can over time cause physical symptoms of pain or illness in the body and hinder the healing process.

Healing Through the Body

One of the most effective ways of working with both traumatic memory and interrupted defensive strategies is through the body. In the sensorimotor approach, special attention is given to stored impulses in the body, and through this, incomplete defensive responses are allowed to complete through what is known as acts of triumph. An act of triumph is done through allowing yourself to experience in the body the impulse of an interrupted defensive response, and then following that impulse to completion. It can feel surprisingly good to complete these acts and often clients report immediate relief from trauma symptoms, as well as more feelings of freedom and less of fear.

Though there certainly is talking involved in sensorimotor trauma work, there is an emphasis placed on the body, which can be strange at first. However, this focus allows for a deep level of healing not possible through talk therapy alone, and once past the initial awkwardness it can be quite freeing. If you, or someone you love, have been diagnosed with PTSD or think you may be experiencing symptoms of past trauma (see Trauma/PTSD for more information), I encourage you to seek support from a therapist trained in trauma recovery right away. Help is available now. No one has to live with the painful symptoms of trauma for the rest of their lives

I have insomnia so I’m up all night. I try and think of ways that I can help other Vets. If you call your docotr or VA every other day, write them e-mails and letters and keep copies of them and once you get fed up (six months is my limit). Write them a letter (intelligent) telling them how unprofessional you feel their service has been and let them know that you are going to file a formal complaint to the head of their department. Then you will get some answers. You don’t have to be rude about it. I think if they send out a letter telling Vets that you are still working their case, is better than not hearing anything from them at all,when you write them or call them you should tell them that. I like e-mails because I can keep a copy of what I wrote to them and the response from them and a date. Save them, they come in handy. Go to the patient advocacy in the VA, that is their job to help you when you feel you are not getting the help you know you deserve. I think they are back logged and they need more workers, but that is not our fault, if we pressure them, then they should pressure the powers that be to get more help, because as soon as one of us go off (hurt or curse) someone we will be labeled crazy. Talk to the Vets around you and try to make their day better, don’t sit around and complain with one another, use that energy to focus on a solution. I have a lot of bad painful days, but I talk myself into good days as much as I can and I pass it on to others when ever I can. I pass on any information that I learn new. Ask to see their supervisors, if you receive an email, save it and it they cc someone on the e-mail they send to you, ensure you add those cc people to the e-mails you send back to them, because I think those cc are people in the know. Don’t give up, that’s what they want you to do. If we tell or children and the children around us not to go into the military because of the way you are treated when you get out, they will have to go back to the draft because no one will want to go in. We deserve better and we have to stand up for it. Civilians in this country don’t have a clue of how hard we work while we are in the military and the things we have to do once we get out. I call and e-mail HLN all the time, I make sure I don’t sound like a lunatic or someone with a vendetta, they know me by my name and they publish my ideas and air my points of view a lot. The Army was a good job for me and helped me grow, but there has to be a better way to treat us once we are out and after we have given up so much to protect our country